Armour Packing Plant

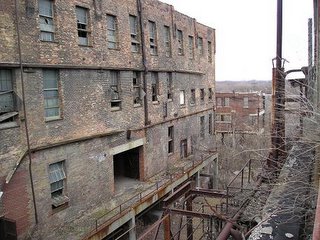

Across the river, in East St. Louis, there exsists a large area dotted with industrial ruins known as National City. If you would have visited this area 100 years ago, you would have seen one of the most well known and innovative industrial centers in the country, with it's state of the art meat packing plants and stockyards. This once great and now crumbling area is often cited as one of the causes for the urban decay taking place in East St. Louis. The Armour Packing plant once made hot dogs - Armour Hot Dogs (I feel like I should be singing that), and is now one of the most spectacular ruins in this part of the c

Across the river, in East St. Louis, there exsists a large area dotted with industrial ruins known as National City. If you would have visited this area 100 years ago, you would have seen one of the most well known and innovative industrial centers in the country, with it's state of the art meat packing plants and stockyards. This once great and now crumbling area is often cited as one of the causes for the urban decay taking place in East St. Louis. The Armour Packing plant once made hot dogs - Armour Hot Dogs (I feel like I should be singing that), and is now one of the most spectacular ruins in this part of the c ountry.

ountry.The day Chris, Tunajive, and I visited Armour was an exciting day before we even left our meeting spot. White Rabbit, creator and administrator of www.undergroundozarks.com, was making the trip up from his hometown of Springfield so that we could show him some of the highlights in St. Louis. It was through White Rabbit's site that our small but illustrious group had met, as we were all active on the Undergound Ozarks forums. Though we had spoken via email, none of us had ever met White Rabbit. He pulled up just as I was taking an impromptu pee, which was quite embarrasing. But what an ice breaker! We all introduced ourselves to him and his girlfriend Hiccup, and then were off to Armour.

I was immediately impressed with the packing plant. It is massive, beautiful in it's crumbling state, and relatively free of any tagging. White Rabbit was impressed as well. "We don't have anything close to this in Springfield," he said. Chris began giving us the grand tour. Armour is really two separate buildings: the pac

king house and the power plant that supplied it with power. Armour was built in 1903 by Chicago industrialist Phillip Armour. He singlehandedly revolutionized the process in which hogs were slaughtered and converted into yummy rods of deliciousness. As opposed to having the slaughtering done at a different plant and then shipped somewhere else for processing, Mr. Armour realized it would be easier to do it all in one place. Packing plants like this were the first industry to use assembly lines. Phillip Armour simplified the process of hog slaughtering and processing by giving one simple task to countless unskilled workers, allowing hogs to be killed, dismembered, and prepared fast

king house and the power plant that supplied it with power. Armour was built in 1903 by Chicago industrialist Phillip Armour. He singlehandedly revolutionized the process in which hogs were slaughtered and converted into yummy rods of deliciousness. As opposed to having the slaughtering done at a different plant and then shipped somewhere else for processing, Mr. Armour realized it would be easier to do it all in one place. Packing plants like this were the first industry to use assembly lines. Phillip Armour simplified the process of hog slaughtering and processing by giving one simple task to countless unskilled workers, allowing hogs to be killed, dismembered, and prepared fast er than it had ever been done before. Different by-products were even used to make different products like Dial soap! Unfortunately, this empire of meat was abandoned like the rest of National City in 1959. It is in relatively good condition when compared to the nearby Hunter Plant, which closed in the 80s and is crumbling to the point unrecognition.

er than it had ever been done before. Different by-products were even used to make different products like Dial soap! Unfortunately, this empire of meat was abandoned like the rest of National City in 1959. It is in relatively good condition when compared to the nearby Hunter Plant, which closed in the 80s and is crumbling to the point unrecognition.We began exploring the packing building first. As we slowly ascended the many floors, we found more and more intersting catwalks and ladders. It's amazing how a ladder can go absolutely nowhere, but because it's there I just have to climb it. At one point, White Rabbit decided to climb out into a portion of the building where the above floors had collap

sed into the room. As he was returning, he somehow cranked his head on a fallen beam and spent the rest of the trip looking as though someone had smashed a ketchup packet on his forehead. I never once heard him complain about his wound. I did, however, hear him tell Hiccup that he was sorry on multiple occasions. Apparently, this was not the first time his adventurous nature had been a source of stress for her.

sed into the room. As he was returning, he somehow cranked his head on a fallen beam and spent the rest of the trip looking as though someone had smashed a ketchup packet on his forehead. I never once heard him complain about his wound. I did, however, hear him tell Hiccup that he was sorry on multiple occasions. Apparently, this was not the first time his adventurous nature had been a source of stress for her.On higher floors we found large trenches in the floor that seemed to run to a series of drains. Always morbid, Tunajive and I decided that these must have been where the blood ran after they slit the hogs' throats

. Not that we have any idea about the process, but we'd like to think we're right. On the highest floor, you can still see the gate where the hogs would file into the large room for god knows what step of the process. There was no real machinery left in this area of the plant, so I didn't get to see the large machines with whirring blades and clubs like I'm sure must have been there at one time.

. Not that we have any idea about the process, but we'd like to think we're right. On the highest floor, you can still see the gate where the hogs would file into the large room for god knows what step of the process. There was no real machinery left in this area of the plant, so I didn't get to see the large machines with whirring blades and clubs like I'm sure must have been there at one time.After the packing building, we entered the power plant. This building is by far the more interesting at Armour, because unlike it's sister it still has all the old massive machines that used to keep the plant running. I've never seen such a collection of industrial equipment so well preserved in one place. This alone makes any visit well worth the trip. We wandered ar

ound this building, actually finding our way into one of the two smokestacks. Though we exited covered in black carbon powder, it was worth it for the feeling of being at the bottom of the massive stack. White Rabbit seemed to want to climb up the ladder that still stretched to the top, but was somewhat unsure of it's stability.

ound this building, actually finding our way into one of the two smokestacks. Though we exited covered in black carbon powder, it was worth it for the feeling of being at the bottom of the massive stack. White Rabbit seemed to want to climb up the ladder that still stretched to the top, but was somewhat unsure of it's stability.We walked up another series of steel staircases and found ourselves on a catwalk above the giant coal hopper. Interestingly, it was still full of coal. I grabbed a handful in case I would have to play Santa this year. Because seriously, where can you find coal this day in age? The higher floors of this building are a

ll the old locker rooms, including one that is only acessible by dropping through a hold in the roof of the plant. Here on the roof, White Rabbit and I both seriously considered climbing the ladder that still remained on the outside of the smokestack, but again we weren't sure how much we could trust the 100 year old rungs. In the end, our good sense got the better of us. White Rabbit was able to show us the power of his digital camera from there on the roof, taking a shot of someone scavenging through the junk that litters the land around the plant. "You wanna see his face?" he asked me. It was amazing how close he was able to get! It looked as though he had bed standing right next to the man when he took the photo. I guess that's what paying a grand for a camera will get you.

ll the old locker rooms, including one that is only acessible by dropping through a hold in the roof of the plant. Here on the roof, White Rabbit and I both seriously considered climbing the ladder that still remained on the outside of the smokestack, but again we weren't sure how much we could trust the 100 year old rungs. In the end, our good sense got the better of us. White Rabbit was able to show us the power of his digital camera from there on the roof, taking a shot of someone scavenging through the junk that litters the land around the plant. "You wanna see his face?" he asked me. It was amazing how close he was able to get! It looked as though he had bed standing right next to the man when he took the photo. I guess that's what paying a grand for a camera will get you.

Armour is one of the more interesting places I've ever explored, and begs many return trips. Whenever I tell someone that I visited an abandoned building in East St. Louis, their eyes widen. The armour plant, however, is well removed from anything else. It sits alone, crumbling yet undisturbed. There are always ideas being discussed by those who discuss ideas about what could be done with the many empty industrial areas of National City. Until then, Armour and the surrounding ruins will remain as a testament to a once great empire of industry.

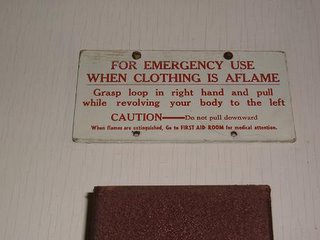

Does anyone else think that this sign is as funny as I do?

Does anyone else think that this sign is as funny as I do? !

!